Every society reveals its anxieties in its exams.

South Korea revealed quite a lot this year.

The English section of the College Scholastic Ability Test, the Suneung, became so difficult that it briefly escaped the country’s borders. The BBC compared it to deciphering an ancient script. The New York Times, with a mix of bemusement and challenge, presented readers with excerpts from the test — a passage invoking Immanuel Kant, another steeped in gaming jargon — and invited them to try solving it themselves.

For many Koreans, this reaction felt embarrassing. For others, vindicating. The world, it seemed, was finally seeing what students had long known: English in Korea is no longer treated as a language. It has become a barrier.

The question at the heart of the controversy is not really about difficulty. It is about purpose. Are we teaching English as a living tool for communication, or as an abstract puzzle designed to separate winners from losers?

For years, the system has quietly chosen the latter. Reading passages have grown denser, sentence structures more tortuous, and multiple-choice options more devious. Speaking, listening and writing — the ways real humans actually use language — have been sidelined.

Students learn how to eliminate distractors, not how to introduce themselves. They master test-taking strategies, not conversations.

The result is a peculiar national paradox: students who score near-perfectly on English exams yet freeze when asked a simple question by a foreigner. Excellence without fluency. Precision without confidence.

This distortion worsened after English was converted to an absolute grading system in 2018. The idea was sensible. English would be treated as a basic competency, not a competitive weapon. The pressure would ease. Private tutoring costs would fall.

Instead, this year’s exam quietly betrayed that promise. The share of top scorers was cut roughly in half, from around 6 percent to about 3 percent. An absolute evaluation had begun behaving like a relative one. The system wanted its rankings back.

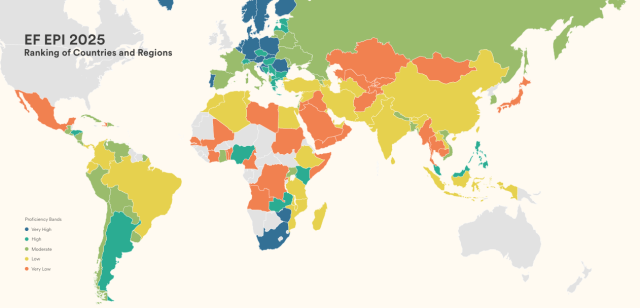

Global data suggest the consequences are already visible. In EF Education First’s 2025 English Proficiency Index, based on millions of adult test-takers worldwide, South Korea ranked 48th out of 64 non-English-speaking countries, with a score of 522 — firmly in the “moderate” range. This places Korea below several countries with far fewer educational resources, and uncomfortably close to the middle of the global pack.

This is not because Koreans do not study English. They do — intensely. But the structure is mismatched to the goal. According to the U.S. Foreign Service Institute, it takes roughly 4,300 hours of study to develop professional working proficiency in a foreign language. Korea’s entire formal education system — from elementary school through university — provides barely a quarter of that.

Time matters. So does direction.

Then there is artificial intelligence, hovering over this debate like a tempting shortcut. Translation apps are improving. AI chatbots can draft emails, summarize articles, even simulate conversation.

It is increasingly fashionable to ask whether English still matters at all. This is the wrong question. The real danger is not that English will become obsolete, but that inequality will deepen.

A 2025 report titled Digital Literacy in the Age of AI warns of what it calls “the AI Empowerment Divide, where only some communities gain the skills and opportunities needed to benefit from the next generation of technology.”

AI does not distribute power evenly. It amplifies existing capabilities. Those who already possess language skills, critical judgment and digital literacy will use AI as leverage. Those who do not will rely on it blindly.

In that sense, English is becoming less optional, not more — especially in an AI-mediated world where evaluating, correcting and contextualizing machine output requires human judgment and linguistic nuance.

What follows is not mysterious. English education needs a philosophical reset.

Classrooms must shift away from treating English as a riddle to be solved and toward treating it as a medium to be used. Speaking and listening must reclaim equal status with reading. Writing must be more than filling in blanks. AI tools, if deployed thoughtfully in public education, can help personalize practice and reduce reliance on private tutoring — but only if access gaps in devices, connectivity and teacher training are addressed first.

Assessment must change as well. In an era when machines can generate polished answers in seconds, evaluating final products alone is pointless. What matters now is the reasoning process: how students interpret information, question sources, and refine ideas — including those produced by AI.

Finally, the English section of the Suneung must remember its original promise. An absolute evaluation should confirm basic proficiency, not reintroduce competition by stealth. When a test breeds aversion rather than confidence, it has already failed.

English is not merely a subject. It is the operating system of global exchange — cultural, economic, and increasingly technological. When a society turns that language into a gatekeeping device, it pays a long-term price.

The world’s amused reaction to this year’s Suneung should not be dismissed as mockery. It should be read as a mirror.

*The author is the managing editor of AJP

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.