From strawberry cakes to lattes, the fruit dominates winter menus.

"Orders are pouring in because it's winter strawberry season. We go through 10 kilograms of strawberries a day," said the owner of a café in downtown Seoul. Winter strawberries grown in greenhouses are known to be especially sweet.

Korea-grown strawberries have also gained global popularity. Strawberry exports surpassed the 100-billion-won ($70 million) mark in 2023, becoming the country's top agricultural export item by value.

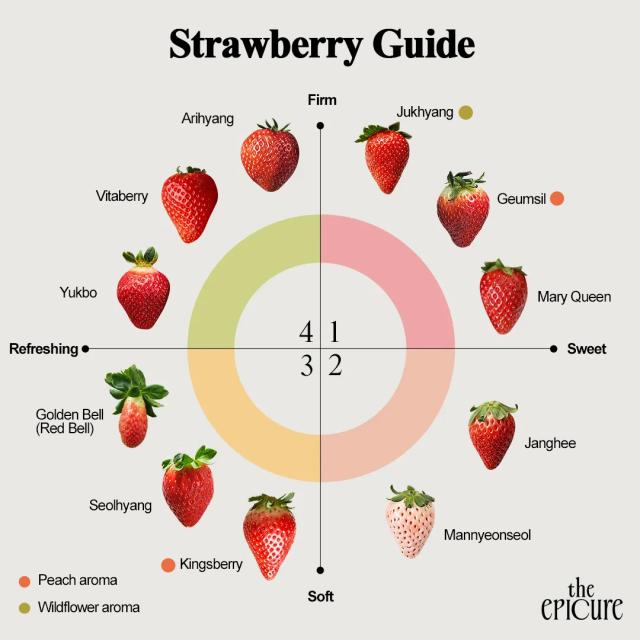

Their appeal lies in freshness and sweetness — the result of advanced breeding technology. Only Korea, Japan and China possess premium strawberry varieties with high sugar content that are widely recognized in global markets. Among them, Korea has secured a competitive edge by developing proprietary varieties such as Seolhyang, Maehyang and Geumsil, establishing what industry officials describe as "sovereignty" in strawberry farming.

Since Seolhyang — a low-acid, juicy variety developed by the Nonsan Strawberry Research Institute under the Chungcheongnam-do Agricultural Research and Extension Services — entered the market, Korea's domestic strawberry variety adoption rate has reached 96.3 percent. Between 2005 and 2020, the country saved an estimated 35 billion won in royalty payments by replacing foreign varieties.

The strawberry "family" has continued to expand, with Maehyang introduced in 2010, Kingsberry in 2012, Sunnyberry in 2016, Vitaberry in 2017 and Geumsil in 2019. Currently, 18 Korean strawberry varieties are registered with the Rural Development Administration.

More than half of Korea's strawberry exports are shipped to Southeast Asian markets such as Hong Kong and Singapore. To maintain freshness, shipments rely on air freight and short-haul routes — a limitation that has capped further export growth.

"If they can't go far, why not grow them overseas?" That question has led Korea's strawberry industry toward smart-farm experiments in the Middle East.

Smart farming offers solutions to those logistical constraints. Water usage is reduced to roughly one-tenth of traditional agriculture, farms can be built in deserts or city centers, and production is shielded from climate volatility. These advantages have drawn strong interest from Middle Eastern countries pursuing food self-sufficiency.

Heating is the key challenge for winter farming in temperate climates — while cooling is the main hurdle in desert regions. Artificial intelligence (AI) has reshaped both.

"Everything is automated based on environmental conditions that replicate natural growing environments through sensors," said Lee Sang-hun, CEO of Agro Solution Korea.

Lee has been running a vertical farm in Abu Dhabi's Al Khatm South district since January 2025.

Sensors collect real-time data on temperature, humidity and soil moisture, which AI systems analyze to automatically maintain optimal growing conditions. Early signs of pests and diseases are detected, while LED light spectra are adjusted according to growth stages to boost energy efficiency. Manual monitoring is largely replaced by data.

Smart farms precisely control temperature, humidity, CO₂ levels and lighting. Vertical farms, in particular, achieve high productivity in confined spaces using multi-tier shelf structures. In conventional setups, fixed growing beds waste 30 to 40 percent of floor space on permanent walkways.

"Vertical farms require more than 5 million won per pyeong in upfront investment for a four-tier structure," Lee said. "That's heavy capital, but the Middle East has the financial capacity."

Lee added that while talks are underway with the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia, large-scale expansion in Southeast Asia is challenging due to high humidity, unstable electricity and limited corporate investment.

"The Middle East is more attractive," he said.

Lee's smart farm in Abu Dhabi uses a "Double Bed" system. Unlike conventional single-row planting, two beds are connected to increase planting density and maximize yield per square meter.

With this setup, 12,000 strawberry plants can be grown in a 75-pyeong (248-square-meter) facility, producing about one ton of strawberries per month.

The potential is significant in a region where food self-sufficiency rates hover around 10 percent. Locally grown strawberries are virtually nonexistent, with imports arriving mainly from Europe and the United States. Long-haul logistics push prices into luxury territory.

"In desert climates where temperatures exceed 40 degrees Celsius and annual rainfall falls below 100 millimeters, traditional agriculture is nearly impossible," Lee said.

Strawberries reach optimal flavor at sugar levels above 10 Brix, he explained, requiring temperature swings between a maximum of 24 degrees Celsius and a minimum of 10 degrees.

"Strawberries are cold-climate plants, so heating isn't necessary," Lee said. "In vertical farms, we mainly focus on cooling. Even in winter, indoor temperatures remain stable — winter is actually ideal."

Although desert heat suggests heavy cooling costs, Lee said insulation makes the difference.

"We use double-layer sandwich panels to block external heat and maintain internal temperatures. There's minimal heat loss."

Electricity costs also favor the Middle East. In the UAE, power for data centers costs about 73 won per kilowatt-hour — less than half Korea's average commercial rate of 172.99 won.

Lee's company is also working with the Korea Institute of Energy Research on a proof-of-concept project to capture waste heat from LEDs. Since LEDs emit only 20 percent light and 80 percent heat, recovering that heat could significantly cut cooling demand.

Automation is also reducing labor costs. While strawberry harvesting still requires human hands, Lee said progress is being made.

"Starting this January at our Iksan farm, robots patrol the facility to identify pest and disease outbreaks and apply treatments only where needed," he said. Full automation of harvesting is expected to take several more years.

K-strawberry exports, which approached 100 billion won again in 2024, are projected to expand further. The Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs has set a target of $21 billion in K-food exports by 2030 and identified the Middle East as a key growth market for fresh fruit.

The Middle Eastern fruit and vegetable market is expected to grow from $17.9 billion in 2025 to $25.8 billion by 2032 — and Korea's smart-farm technology may offer the blueprint for growing strawberries where none could grow before.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.