AI is no longer defined solely by algorithms. As large-scale deployment accelerates, data centers and power infrastructure have become decisive constraints. AJP examines how energy capacity is reshaping the U.S.–China AI rivalry — and what lessons South Korea must draw as time tightens in the global race.

SEOUL, December 29 (AJP) - AI is no longer constrained mainly by algorithms or chips. As data centers scale to industrial size, electricity has emerged as the decisive bottleneck shaping global competition. In that race, China currently holds a structural advantage, while the United States is scrambling to realign its energy policy to sustain its lead in artificial intelligence.

AI-focused data centers already consume as much electricity as heavy industries such as steel or petrochemicals, and their demand is projected to more than double by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency. By the end of the decade, global AI infrastructure is expected to require more than 700 terawatt-hours (TWh) of power annually — exceeding Japan’s total electricity consumption today.

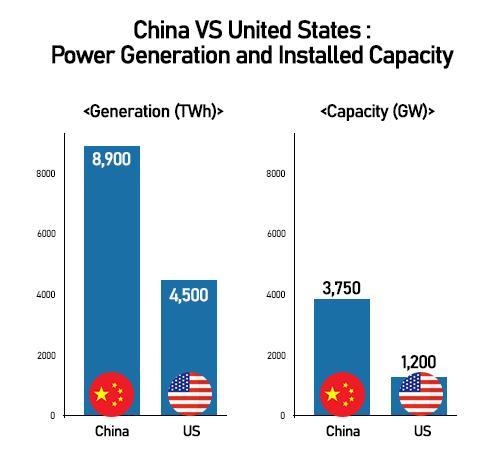

China enters this phase with unmatched scale. In 2023, it generated about 8,900 TWh of electricity, nearly twice the U.S. total of roughly 4,500 TWh. Its installed power capacity stands at about 3.75 terawatts, supported by simultaneous expansion across coal, solar, wind and nuclear energy.

Beijing is pushing ahead with nuclear construction at a pace unmatched globally, with 34 reactors under construction and nearly 200 more in planning. It also installs more than 100 gigawatts of solar capacity and about 60 gigawatts of wind capacity each year. China’s solar manufacturing capacity alone exceeds 1,000 gigawatts, compared with about 26 gigawatts in the United States.

This expansion is reinforced by an extensive ultrahigh-voltage transmission network stretching more than 45,000 kilometers, enabling electricity to flow from inland power bases to coastal data-center clusters. Under the government’s “East Data, West Computing” strategy, regions such as Inner Mongolia offer long-term power contracts at around 3 cents per kilowatt-hour, far below typical U.S. rates.

China now adds more electricity demand each year than the total annual consumption of Germany. Entire rural provinces are blanketed with rooftop solar, and in some cases a single province generates power on a scale comparable to India’s nationwide output.

The United States, meanwhile, is attempting to realign its AI competitiveness around energy availability rather than only compute. Washington’s new approach centers on three pillars: expanding natural-gas generation near data centers, accelerating next-generation nuclear such as small modular reactors (SMRs), and positioning the Department of Energy (DOE) as the coordinating hub for AI-energy infrastructure.

Hyperscale companies including Amazon, Microsoft and Google have begun planning or acquiring natural-gas plants directly adjacent to AI clusters to secure long-term baseload power, an approach meant to bypass local grid congestion. In parallel, the DOE is funding SMR development to supply 24/7 nuclear power to future AI facilities, treating nuclear as a strategic enabler for compute scaling.

The Biden administration has also released regulatory orders to speed up grid-modernization projects, reduce transmission permitting timelines, and create “AI-energy corridors” capable of supporting multi-gigawatt demand. These measures reflect a broader shift: U.S. policymakers increasingly view electricity as part of national AI security, not just industrial infrastructure.

The United States, by contrast, remains the global center of AI model development and advanced semiconductor ecosystems, but its energy system is increasingly a constraint. The country has roughly 1.2 terawatts of installed generating capacity and benefits from abundant natural gas and nuclear resources. Yet more than 70 percent of U.S. transmission lines are over 25 years old, and renewable-energy projects face permitting backlogs exceeding 2,000 gigawatts.

Data-center growth is also highly concentrated geographically. Nearly half of U.S. capacity is clustered in Northern Virginia, Dallas, Phoenix and Silicon Valley, raising grid congestion risks as hyperscale facilities increasingly require between 100 and 500 megawatts each.

As AI models scale toward trillion-parameter systems and continuous real-time training, electricity — not chips — is becoming the binding constraint. Training GPT-4 alone is estimated to have consumed more than 50 gigawatt-hours of electricity, roughly enough to power San Francisco for three days. By 2028, AI-related activity is projected to consume electricity equivalent to 22 percent of all U.S. households.

Recognizing these limits, Washington has begun reframing AI competitiveness around energy infrastructure. Recent executive orders on artificial intelligence and energy call for removing regulatory barriers and accelerating the buildout of power systems needed to support large-scale computing.

The Department of Energy has launched a plan to co-locate data centers with energy infrastructure through public–private partnerships. Under the initiative, AI facilities would be developed on DOE-managed sites offering land, grid access and proximity to national laboratories, which play a central role in energy and materials research.

The department is seeking input from data-center operators, utilities and the public through a formal request-for-information process, with the aim of launching the first operational AI infrastructure hubs by the end of 2027.

Officials argue that closer coordination between energy developers and computing firms will be essential to sustain AI growth while maintaining grid stability and affordability. Co-locating data centers near research facilities is also expected to accelerate advances in next-generation power systems and computing hardware.

As artificial intelligence becomes embedded across the global economy, the competitive frontier is shifting from algorithms to kilowatts. Countries capable of delivering stable, low-cost, multi-gigawatt power at scale will hold a decisive advantage in shaping the next phase of AI development.

China’s centralized planning model allows rapid mobilization of land, transmission and generation capacity. The United States, by contrast, must navigate fragmented permitting regimes and aging infrastructure even as demand surges. The widening gap underscores how energy — once a background input — is fast becoming a core determinant of leadership in the AI era.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.