SEOUL, January 06 (AJP) - South Korea’s foreign-exchange reserves fell by nearly $3 billion in December, marking the largest monthly decline among major reserve-holding economies and underscoring the cost of aggressive market intervention to defend the won.

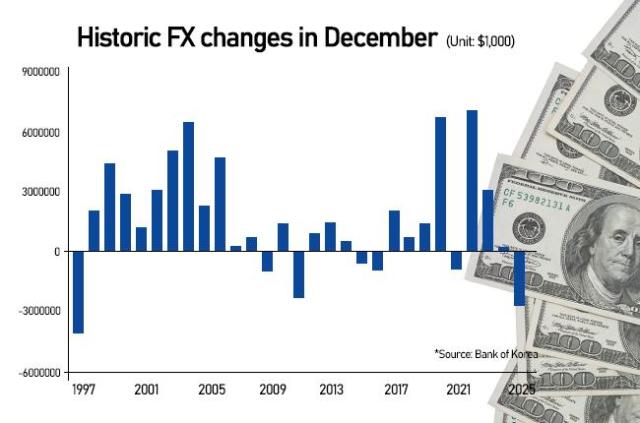

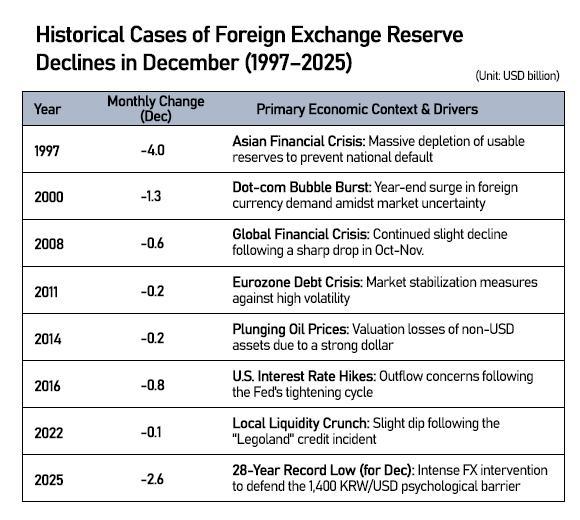

According to data released Tuesday by the Bank of Korea, the country’s FX reserves stood at $428.05 billion at end-December 2025, down $2.6 billion from the previous month. While the headline figure remains substantial, the contraction represents the second-steepest December decline on record, surpassed only by the nearly $4 billion plunge during the 1997 Asian financial crisis, when South Korea sought an IMF bailout.

The drawdown is notable not only for its size but also for its timing. December is typically a month when global financial institutions build up foreign-currency buffers to meet capital-adequacy requirements under Bank for International Settlements Basel III rules, which recommend a common equity Tier 1 ratio of at least 10.5 percent, including a 2.5-percentage-point capital conservation buffer introduced after the 2008 global financial crisis.

In recent years, South Korea followed that seasonal pattern. FX reserves increased in December 2023 and 2024, and even during periods of acute stress the year-end drawdowns were modest. During the 2022 “Legoland” municipal debt default, which rattled domestic credit markets, December reserves fell by just $140 million. At the height of the 2008 global financial crisis, the December decline was limited to about $600 million.

An outlier among major reserve holders

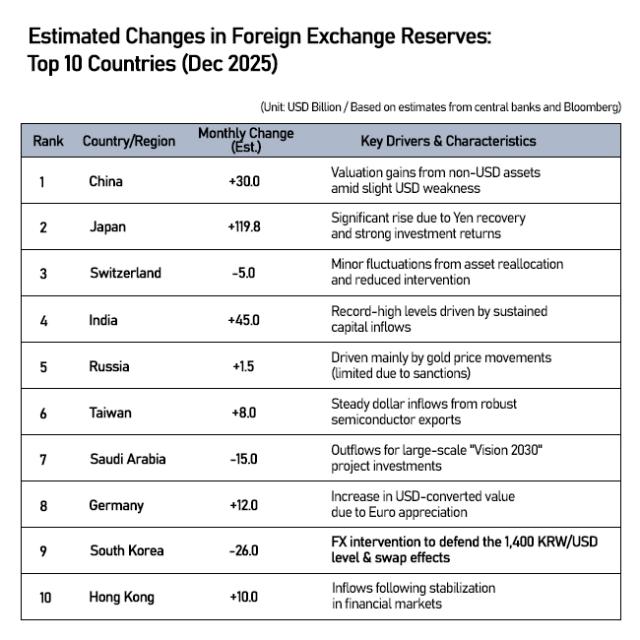

The divergence between Seoul and its peers was stark. China, the world’s largest reserve holder, added roughly $30 billion to its reserves in December. Japan, ranked second, increased its holdings by around $120 billion, while India added $45 billion, the second-largest increase after Japan.

Even Russia, in war-related hemorrhage and sweeping sanctions, recorded a net increase of about $1.5 billion in reserves. The comparison suggests that Korea drew down reserves more aggressively than economies grappling with far more severe external shocks.

Other countries did post declines, but for fundamentally different reasons. Switzerland saw a roughly $5 billion drop, largely reflecting valuation effects from a stronger Swiss franc and a weaker U.S. dollar, rather than active intervention. Saudi Arabia’s estimated $15 billion decline reflects deliberate spending to finance large-scale projects such as the Neom giga-city.

Korea’s case stands apart. The reserve loss was driven primarily by direct and sustained intervention in the currency market to curb the won’s slide amid renewed dollar strength following the U.S. military operation in Venezuela.

Market stability remains a key concern for regulators. As of September, South Korean banks posted a total capital ratio of 15.87 percent, according to the Financial Supervisory Service, a level that appears comfortable on paper.

However, during its annual consultation in November, the International Monetary Fund urged Seoul to maintain even higher buffers, citing rapidly rising household debt—now estimated at 2,000 trillion won (about $1.4 trillion)—which is growing faster than in most advanced economies.

If government intervention continues, analysts warn that FX reserves could remain under pressure through the end of January. The broader impact on the private financial system may become clearer in March, when the FSS releases updated capital-adequacy data for banks.

“Measures to address exchange-rate volatility led to the decrease in reserves,” the Bank of Korea said in its statement.

A central-bank official, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the private and institutional sectors are expected to maintain precautionary measures until the exchange rate stabilizes, but declined to comment on how deeply the interventions may be affecting banks’ capital positions.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.