On Sunday, Lee posted a reflective yet firm message on X, formerly Twitter, calling for a national debate on a proposed “sugar levy” aimed at curbing excessive consumption of sweetened beverages. “The more difficult the issue, the more we must discuss it,” he wrote, citing a World Health Organization recommendation for steep global price hikes on sugary drinks and alcohol by 2035.

Social-media politicking itself is hardly new in Seoul. Korean politicians have long used online platforms as unfiltered arenas for attack and mobilization. What is new is the scale and centrality of presidential participation.

To critics, however, the shift signals something broader: a deliberate attempt to set the national agenda through direct public address, bypassing cabinet deliberation, legislative review and media scrutiny.

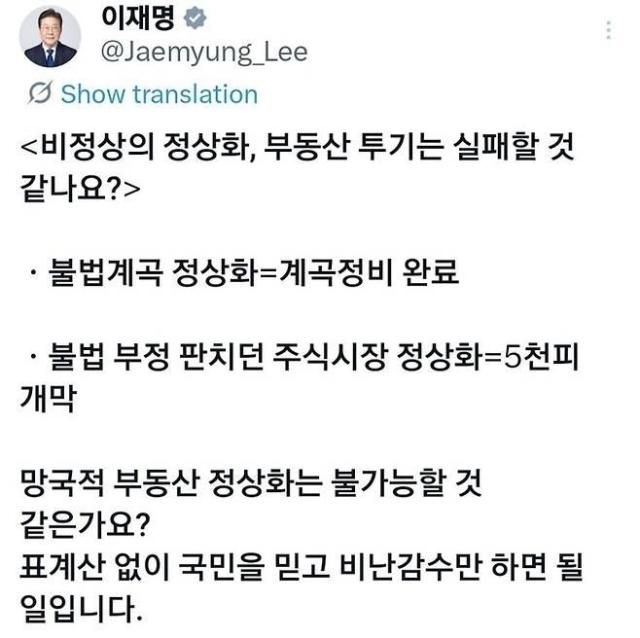

Lee’s recent posts on the sugar levy, housing policy and administrative restructuring have drawn both praise and backlash. His messages — often lengthy, impassioned and sharply worded — share a consistent theme: impatience with intermediaries, whether political or journalistic.

Responding to criticism that the sugar levy amounted to a disguised tax hike, Lee argued that “a tax and a burden charge are fundamentally different,” warning against debate shaped by “distortion and framing.” Elsewhere, he rebuked outlets questioning the end of a real-estate tax exemption, accusing them of “defending ruinous speculation.”

When the opposition People Power Party labeled his remarks “provocative populism,” Lee replied on X: “Enough with ruinous real-estate speculation and outdated red-baiting. It’s time to move on.”

The tone is unmistakably combative, the pace relentless. On some mornings, Lee posts three separate messages — all drafted, aides say, by the president himself.

To detractors, this amounts to governing by post: impulsive, emotional and dismissive of institutional checks. To supporters, it is communicative leadership — a president visibly accountable in real time.

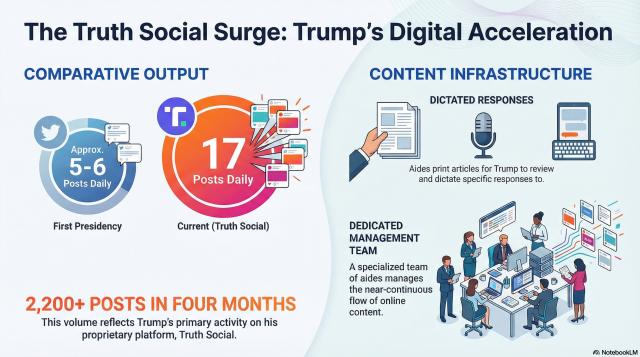

Lee’s assertiveness fits a broader global shift. Leaders worldwide have increasingly turned to social media as tools of direct, performative governance. Few exemplify this more starkly than Trump, who, according to The Washington Post, posted more than 2,200 times on Truth Social during the first four months of his second term — roughly 17 posts a day, triple his rate during his first presidency.

Alex Tahk, a political scientist at the University of Wisconsin, describes this as a modern extension of presidents “going public” — appealing directly to voters to shape agendas and pressure institutions. “Social media makes that process faster and more personalized,” he said, “with far fewer journalistic gatekeepers.”

But the power cuts both ways. “By making positions public and emotionally charged, leaders reduce room for compromise,” Tahk warned. “It can undermine negotiation more than it facilitates it.”

That risk is acute in South Korea’s polarized political climate. Lee’s forthright tone mirrors a global move from closed-door policymaking toward performative governance, where visibility and conviction often rival coalition-building in importance. “Highly confrontational communication,” Tahk noted, “raises the political cost of bipartisan bargaining.”

Lee’s posts often compress intricate fiscal or housing policies into moralized soundbites, tapping what Lu calls the “participatory psychology” of social media — a space where citizens become active, emotionally engaged participants rather than passive audiences.

In such an environment, even serious policy proposals can take on the pulse of campaign rhetoric. Tahk calls this “agenda politics through emotional framing.” “Leaders signal direction and energy,” he said, “but the cost is that complex issues become simplified into moral binaries—fair versus unjust, patriotic versus corrupt.”

Agenda-setting through social media can privilege attention-grabbing topics over long-term governance,” Lu notes. “It blurs the line between informing the public and performing for them.”

That blurring extends beyond content to tempo. Lee’s posting frequency — sometimes several times a day — reflects a presidency operating at the rhythm of the digital news cycle rather than the slower cadence of policy deliberation. Communication becomes continuous, but comprehension more fleeting. Each post triggers immediate responses: ministries scrambling to clarify, pundits to interpret, supporters and critics to mobilize.

The presidency becomes a hub of perpetual mediation.

Unlike Franklin Roosevelt’s carefully timed fireside chats or Ronald Reagan’s choreographed television addresses, today’s digital presidency operates in an algorithmic, fragmented and perpetual environment. There is no single national audience, only segmented feeds optimized for engagement.

Lee’s embrace of this landscape is deliberate. Since his days as mayor of Seongnam and governor of Gyeonggi Province, he cultivated a reputation for online accessibility. As president, that instinct has evolved into a daily rhythm of agenda-setting posts, often paired with news articles he critiques or reframes.

Cheong Wa Dae insists this is transparency, not theatrics. Critics see spectacle. The tension between the two may define Korea’s emerging media presidency — one where policy debate unfolds in public view, but where deliberation grows harder the louder the conversation becomes.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Press All rights reserved.